Tackle graduate unemployment

Our higher education system is converting workers to ‘willingly unemployed’ people and needs serious attention

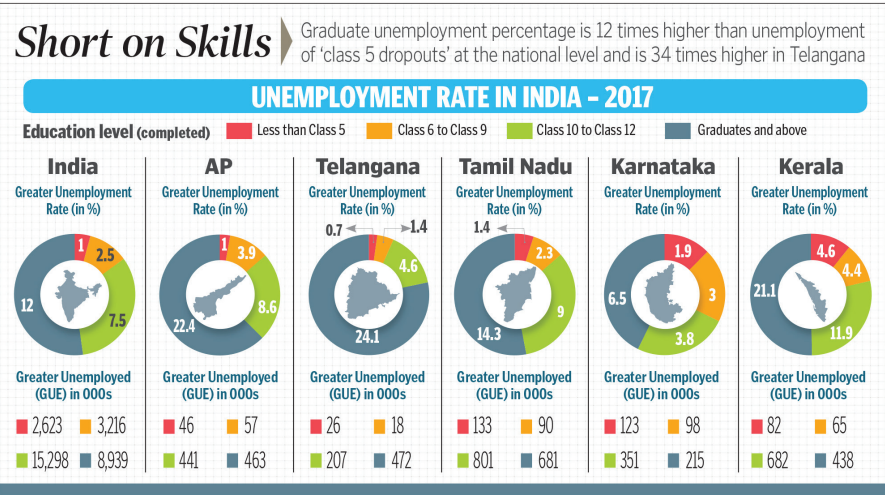

Recently, a national newspaper published a story on graduate unemployment in Telangana with the headline ‘Reality Check- Is TS job ready?’ In the Southern States, the Greater Unemployment Rate (GUER) — unemployment of those actively seeking a job and those willing to work but inactive in the job market — was far higher among graduates than school dropouts. This is the conclusion of ‘Unemployment in India – A statistical profile’ – a report prepared by the BSE and Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE).

For example, in Telangana, 24.1% of the graduates seeking work are unemployed, which is 34 times the percentage of ‘class 5 dropouts’ unemployed. The story is no better in Tamil Nadu, where the Graduates GUER% is 14.3%, which is 10.2 times higher than GUER% for ‘class 5 dropouts’.

Why it’s happening

In 2009, I visited a small village in Dausa district of Rajasthan to study rural unemployment. I met the Sarpanch, Gangaram, a BA graduate, and his brother, an MA. They were idling in the village and refused to work in the fields or do any temporary work because they were graduates, while their entire family was at work! This was when I realised how our higher education system is converting workers to ‘willingly unemployed’ people.

The shock was deeper when I learned why they chose their major. The first bus reached Jaipur at 10 am and the last left at 3 pm. Political History in Hindi medium was the only course available at the University between those timings. It was a choice of convenience, not career.

An Unrecognised Phenomenon

The root cause is the correlation between employability and employment used by policymakers. In European countries with low population growth, right skilling leads to employability, which leads to employment. This is not valid for India.

The second reason is the reliance on generic employability reports from agencies like Nasscom or the ‘India Skills Report 2018’. These reports conclude that skill deficiency is the cause for unemployment. While basic skills are a problem, this narrative is only a small part of the issue and is the root cause of our flawed skill policy.

Why Do I Think So?

Skills can be taught in schools, but they can be grounded only in a live job. Consider the story of Sashi, a graduate from Kerala who came to Mumbai. He couldn’t speak Hindi or English and knew accounting only in Malayalam. I helped him get a job because his family was desperate.

Six months later, he was the darling of the company. He worked 14 hours a day, learnt English, mastered the computer, and spoke good Hindi. In two years, his salary doubled. The first job is the key to skills. Without a job, skills are not grounded.

The Concept of Role-Specific Training

Generic employability assessments are useful for high-end jobs like software or consulting, but not for entry-level back office or ‘feet on street’ sales jobs. The real test should be to train a person on a specific job, let them work for three months at any salary, and then assess their employability against that specific role.